“So, what are you working on?”

It’s a pretty common question when you work at Smithsonian Exhibits. Usually, the answer is something like “A great show at the Hirshhorn!” or “We just kicked off a new project with the Zoo!” When I told my friends that I was working on a new section about multi-agency partnerships for The FBI Experience, they reacted with:

“… that’s not the Smithsonian.”

And of course, they’re right: the FBI is not the Smithsonian, but they are a federal agency, which means we are able to work on their exhibitions under certain circumstances.

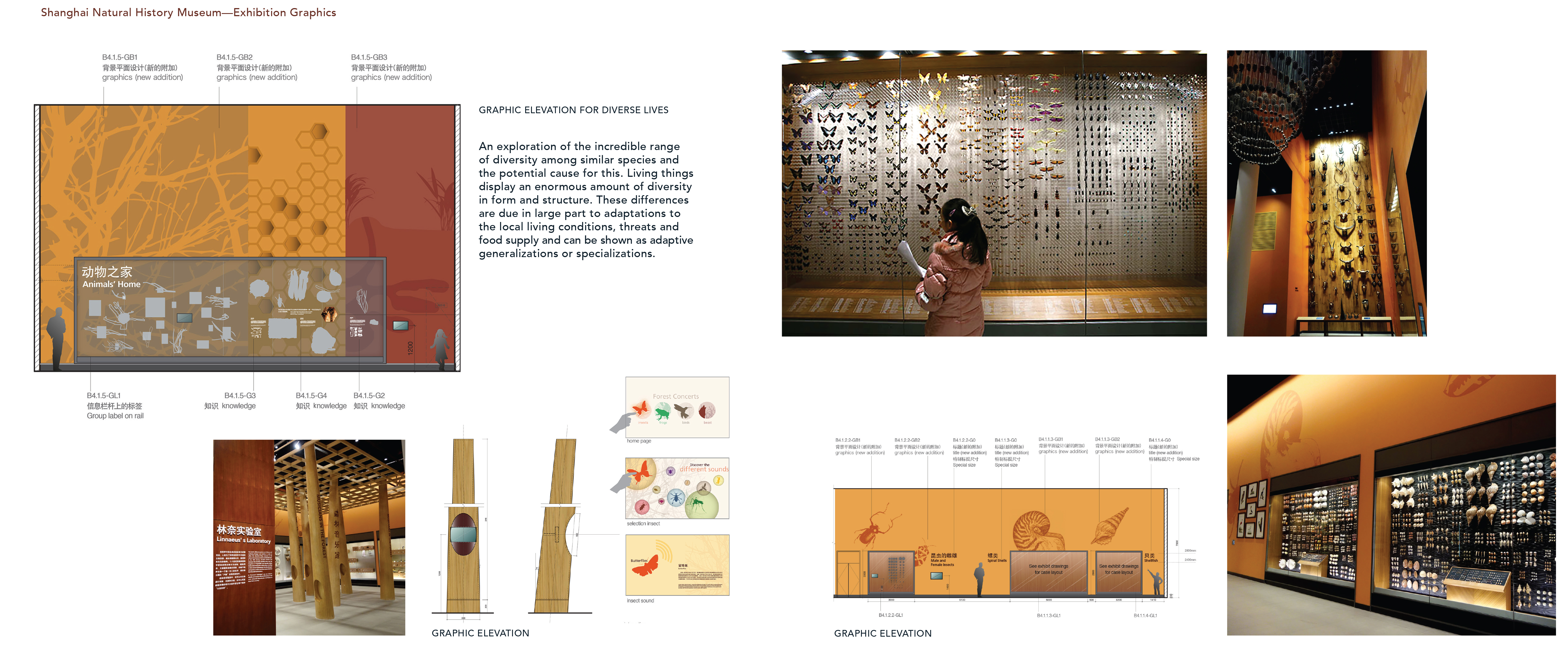

Smithsonian Exhibits’ primary focus is, obviously, the Smithsonian. Our priority is to help our museums, galleries, offices, cultural centers, libraries, and … well, you get the picture: we have a lot of moving parts, and we love to help those parts get their exhibitions up and running. We are, however, also able to partner with federal agencies if their end product is an exhibition on view to the public.

This is particularly handy for agencies that want to set up exhibitions for the first time, but haven’t yet hired museum staff, or perhaps don’t plan on staffing an exhibition once it is open. Provided the work aligns with our missions and goals and we have the capacity to take on the project and a variety of financial requirements are met—I won’t bore you with those details—we can take on the project. In other words, it isn’t a common occurrence, but we do have the occasional outside exhibition. (These outside projects are managed through the Smithsonian’s Office of Sponsored Projects (OSP) through an Inter-Agency Agreement contracting protocol.) When the FBI came to us to discuss opening an exhibition to the public, we were happy to realize that their project met all of the above requirements.

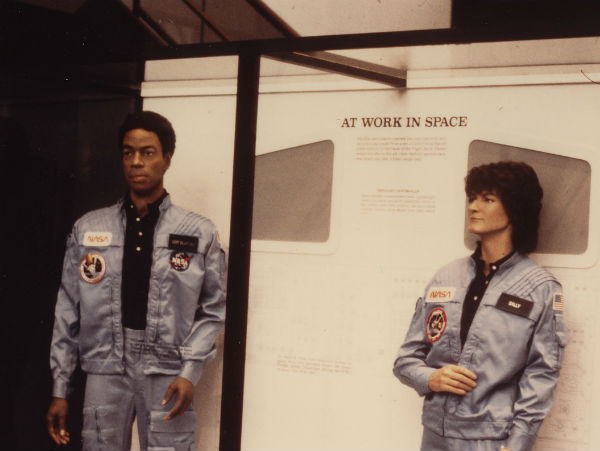

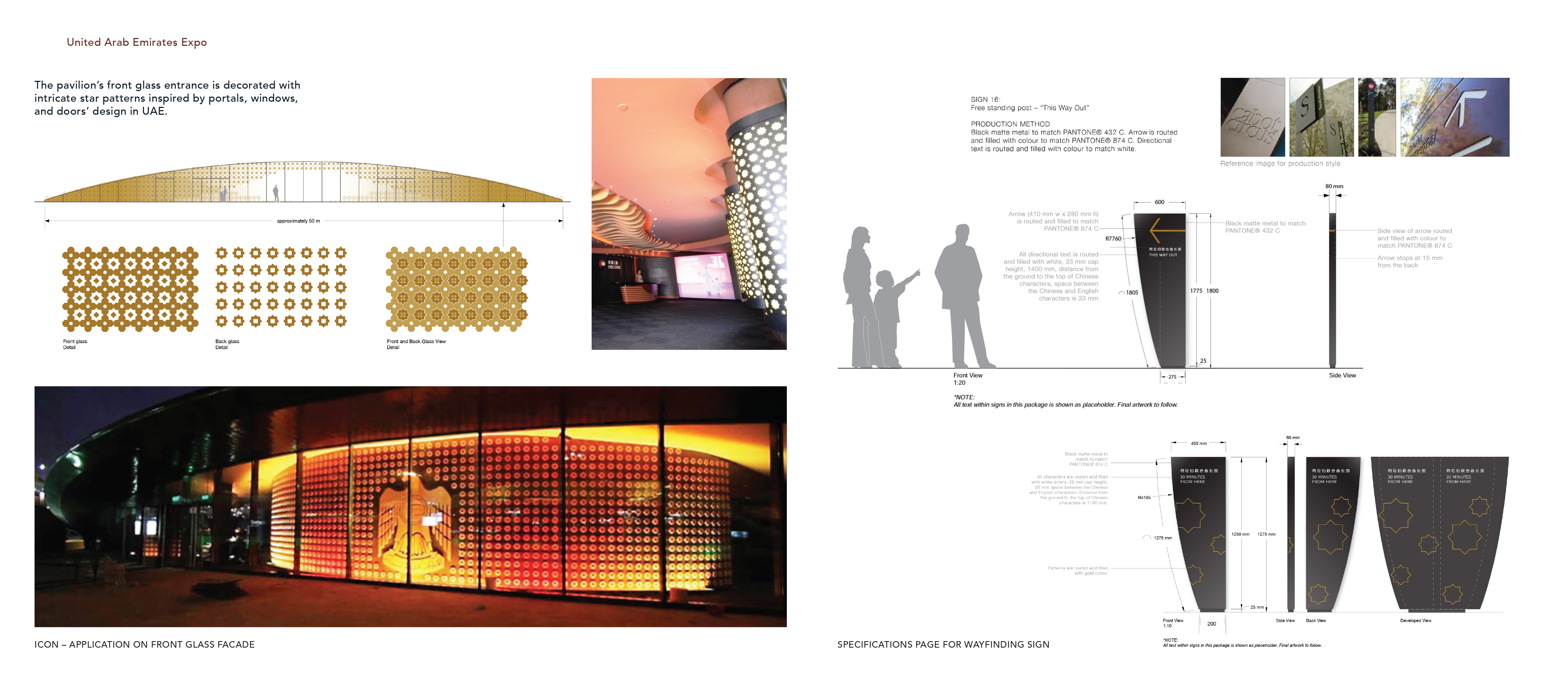

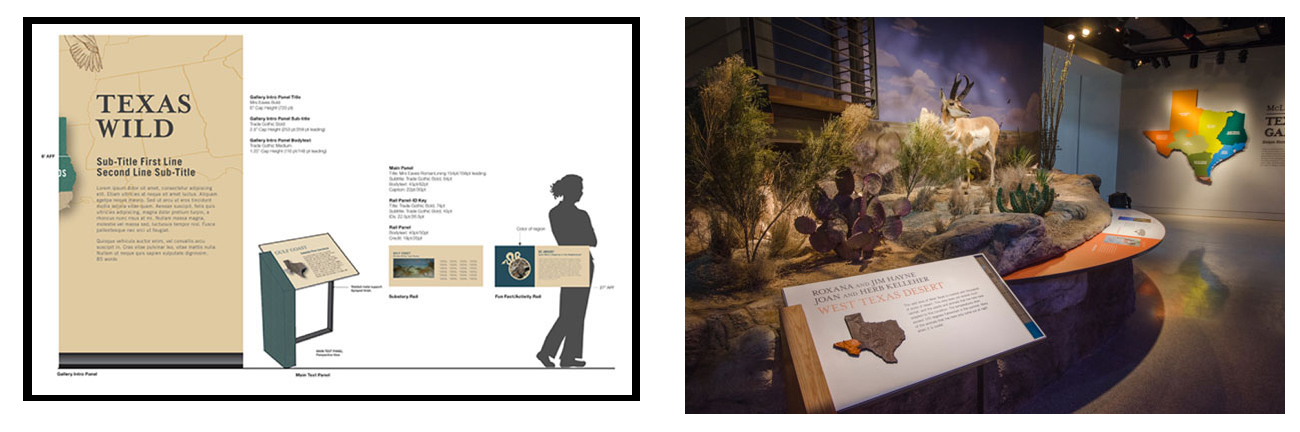

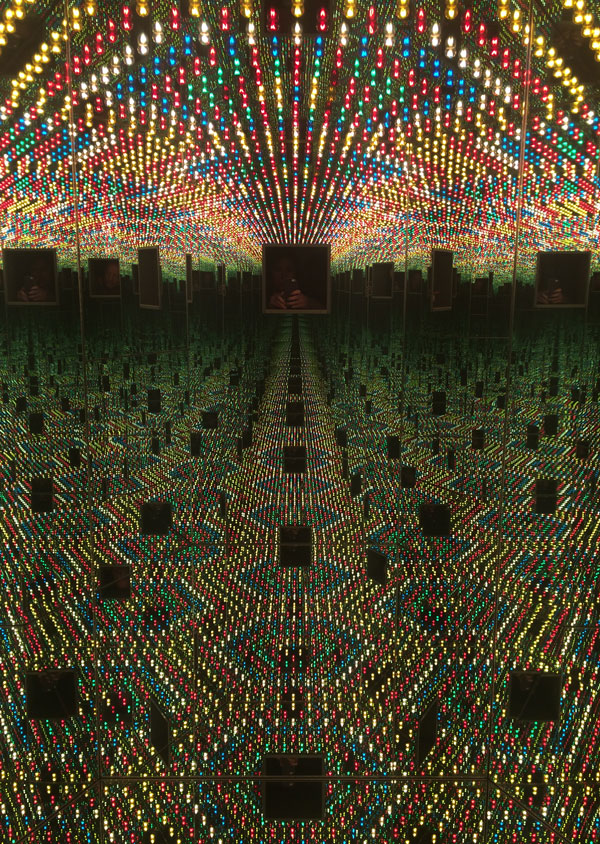

For years, the FBI’s iconic tour had been one of the most popular tours in Washington, D.C. After the 9/11 attacks, the FBI had to shutter the tour due to security concerns. After a lengthy hiatus from welcoming the public into Headquarters, the FBI decided to create an exhibition to explain how the FBI works today. Smithsonian Exhibits was able to partner with the Bureau to create a brand-new exhibition. The FBI Experience opened in June 2017 on two floors of the Headquarters building.

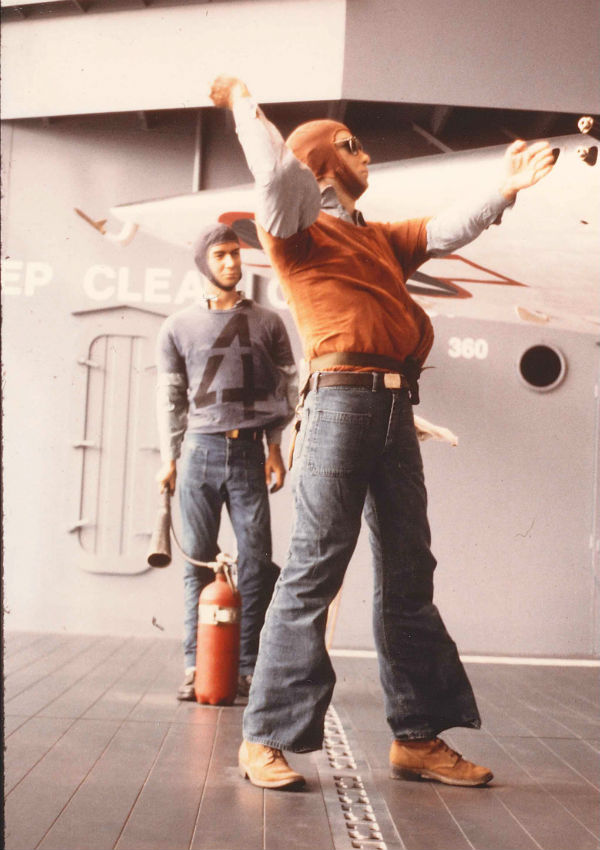

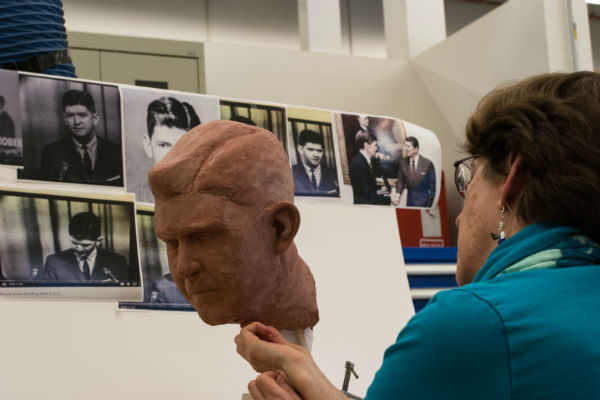

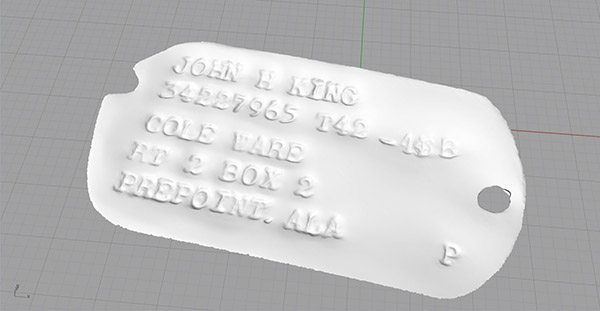

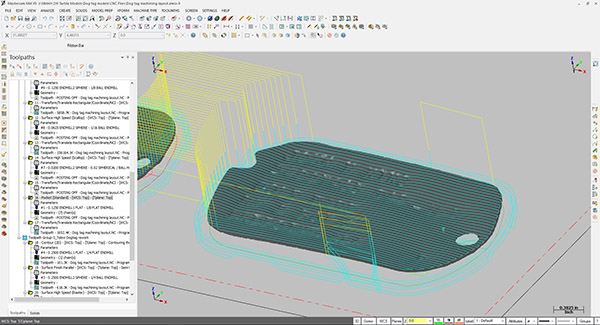

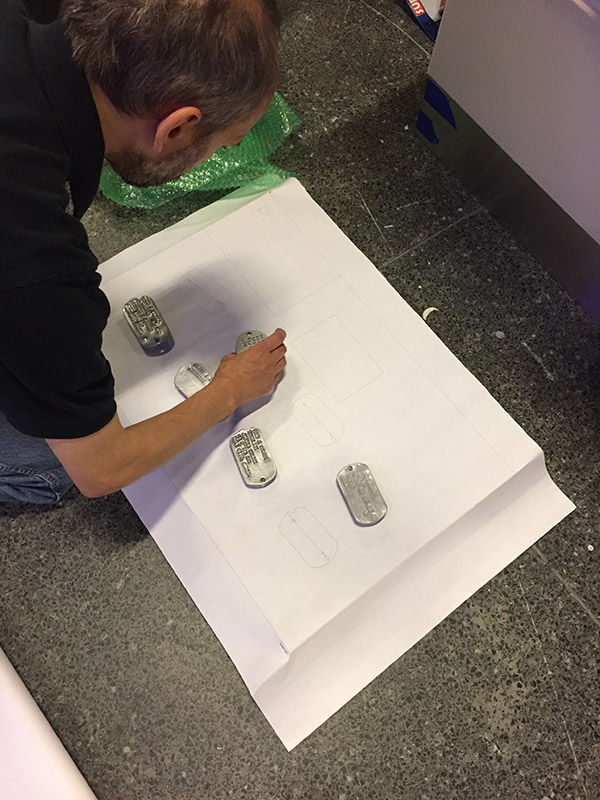

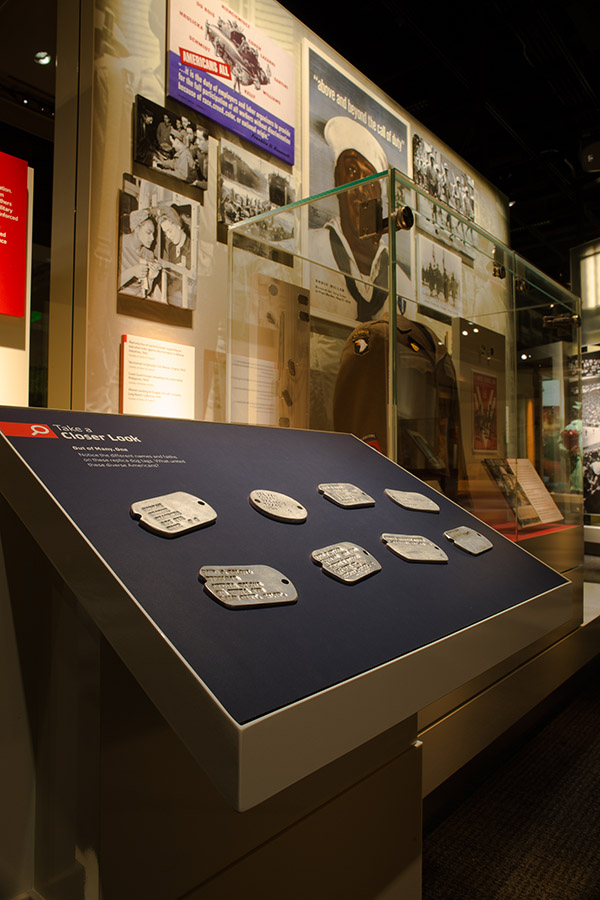

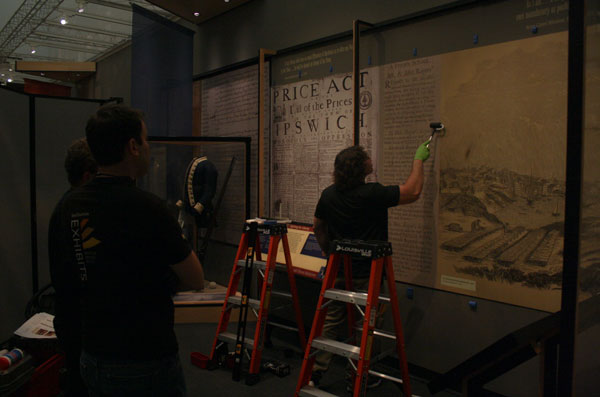

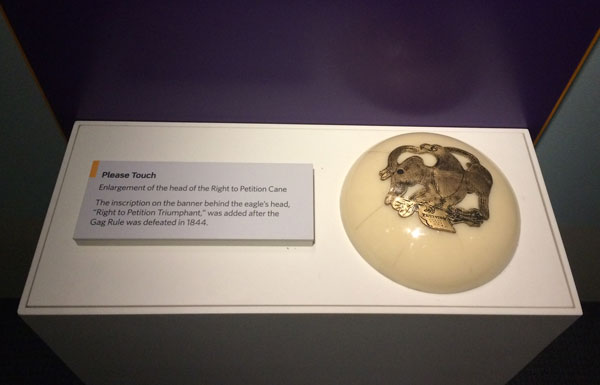

Recently, the FBI acquired objects for use within a new section on multi-agency partnerships. This section explores some of the ways the Bureau works with other agencies and law enforcement departments. By building on each other’s strengths, the FBI, local police, and other agencies can solve crimes and take down criminal organizations more effectively. Each group brings their own expertise to the situation, and that makes a better team.

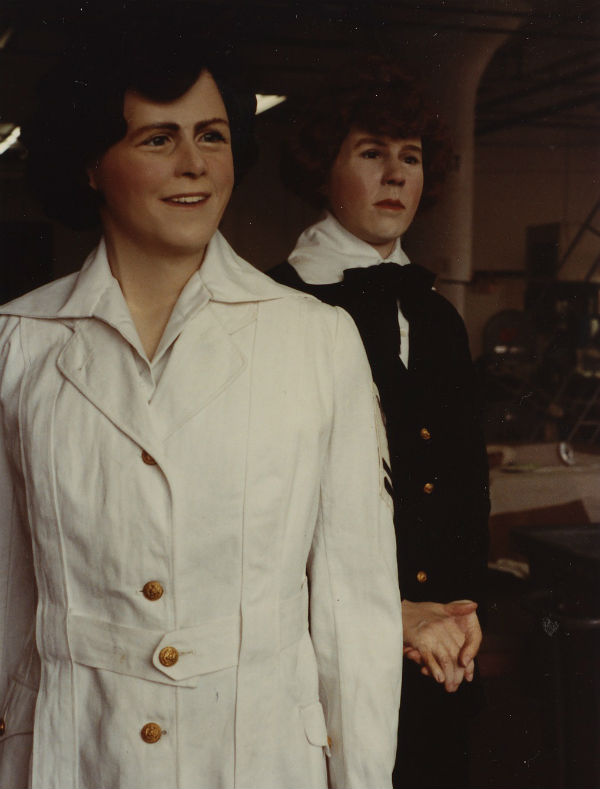

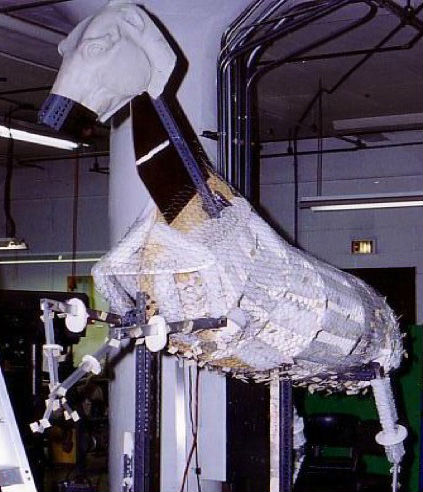

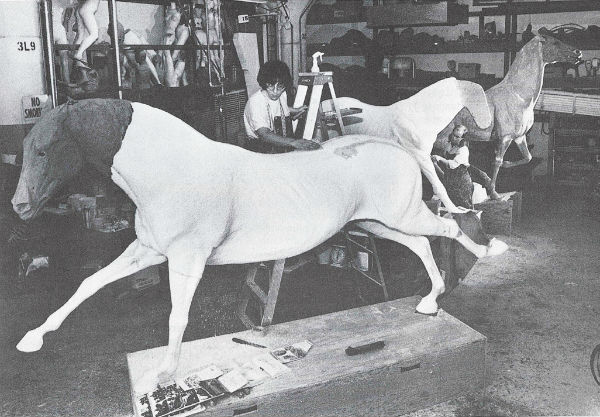

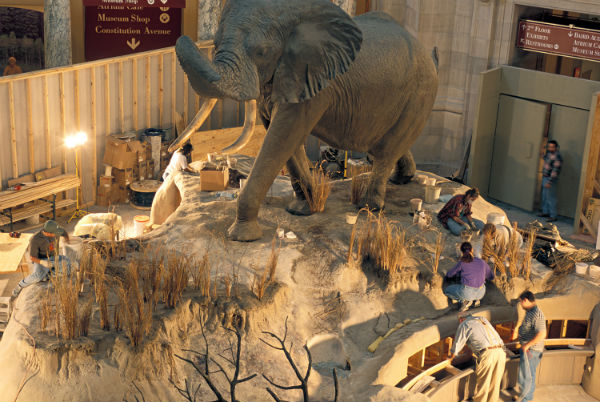

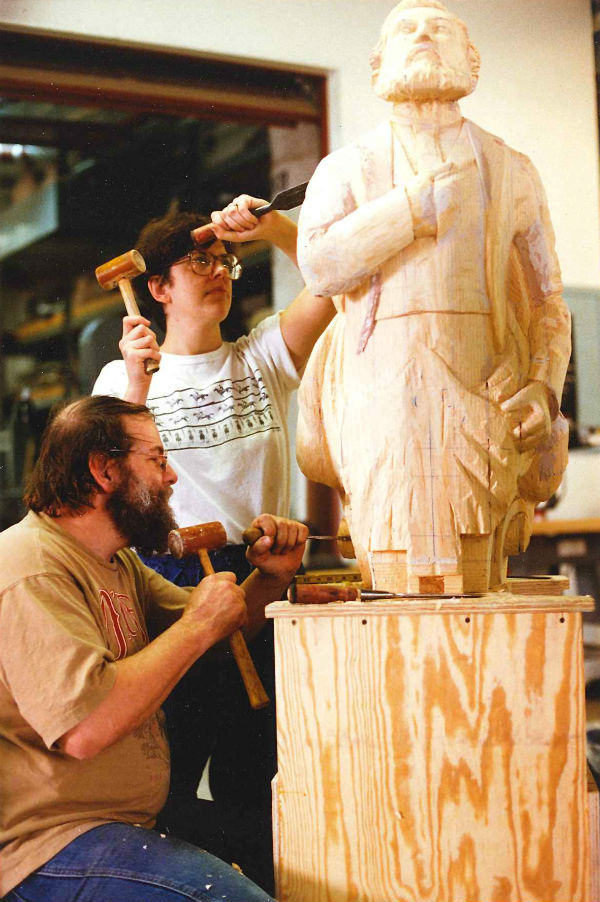

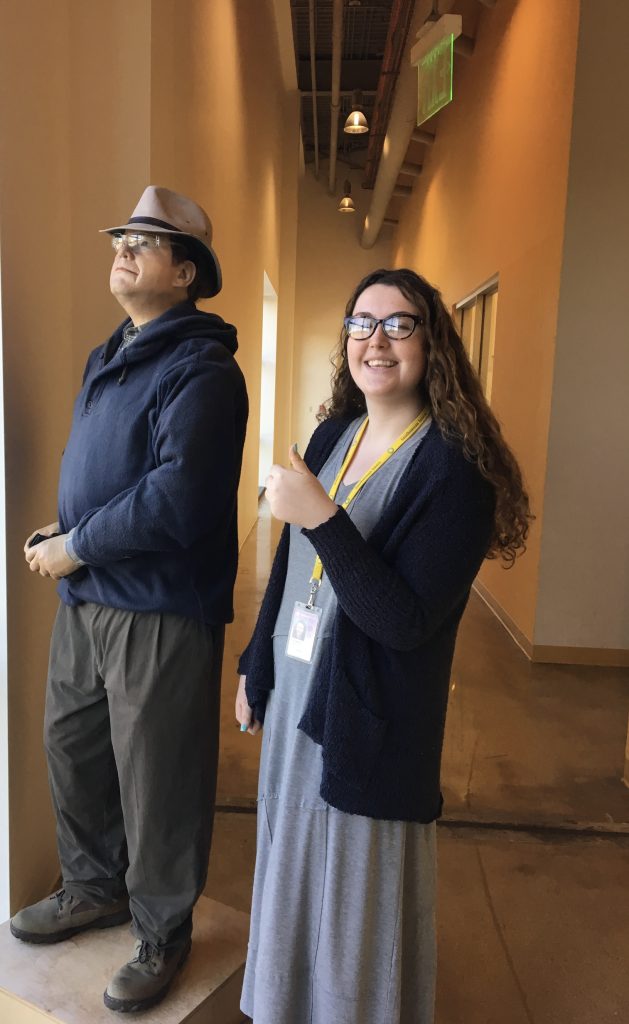

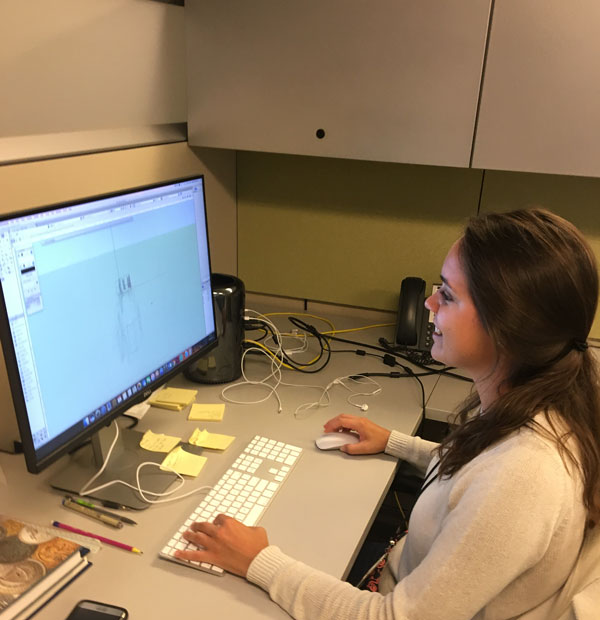

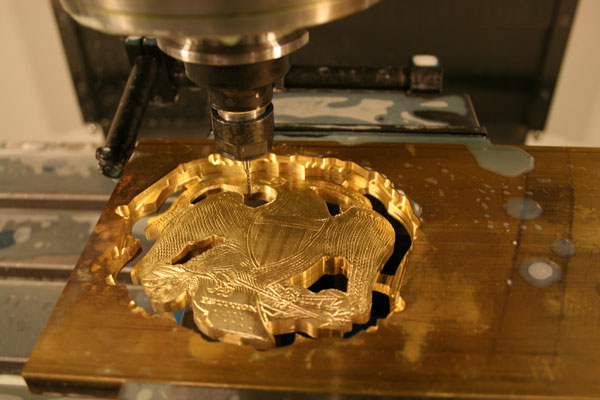

Really, that’s what we’re doing with the FBI, too (albeit in a much, much less crime fight-y way). Inter-agency partnership allows for each group to bring their best parts to the process. The FBI brings their practices and history; Smithsonian Exhibits provides exhibit development and design, scriptwriting, project management, custom artwork, and mount making. By working together throughout the phases of this project, we can achieve the best possible outcome.