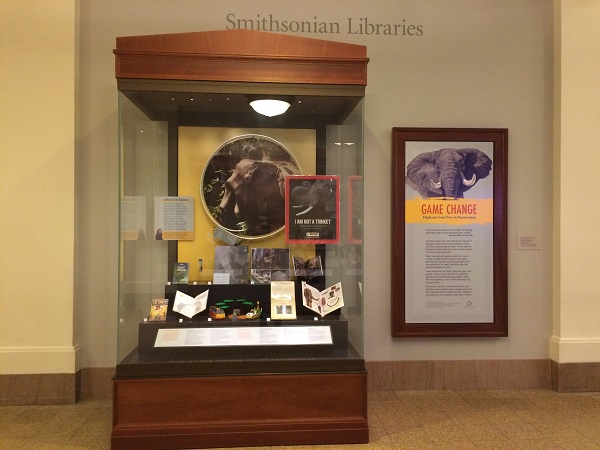

This year, Smithsonian Libraries celebrated its 50th anniversary as a unified library system by opening not one, but two exhibits: Game Change: Elephants from Prey to Preservation and Magnificent Obsessions: Why We Collect. Smithsonian Exhibits (SIE) was thrilled to be asked to design, edit, and produce the exhibits. Here’s our tale . . . (It was the best of times!)

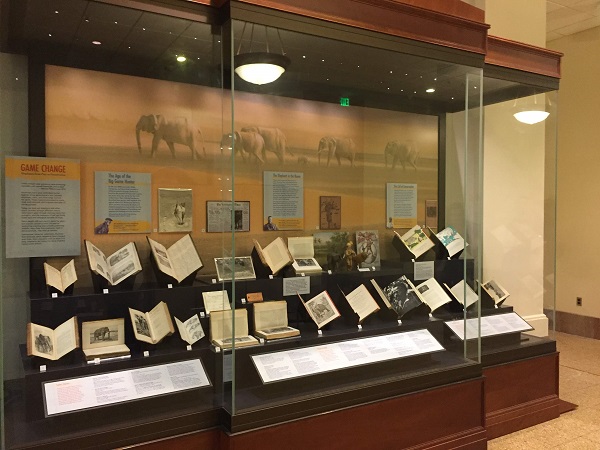

Both exhibits feature books from Smithsonian Libraries’ collections, but they deal with very different subjects.

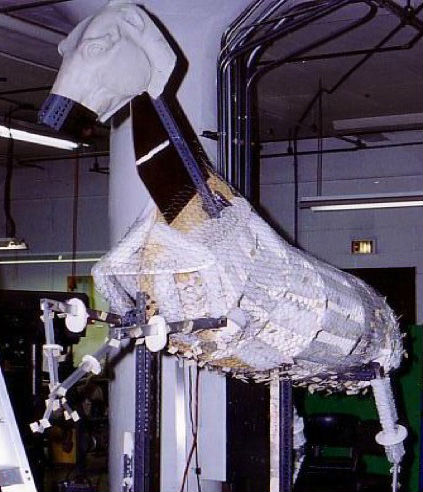

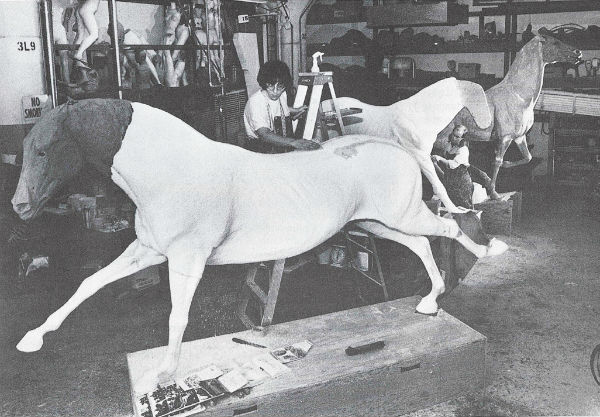

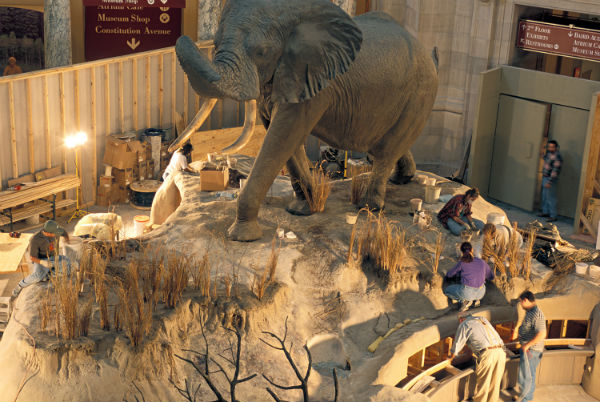

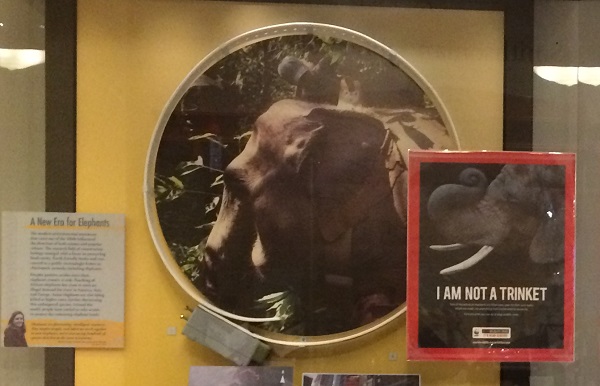

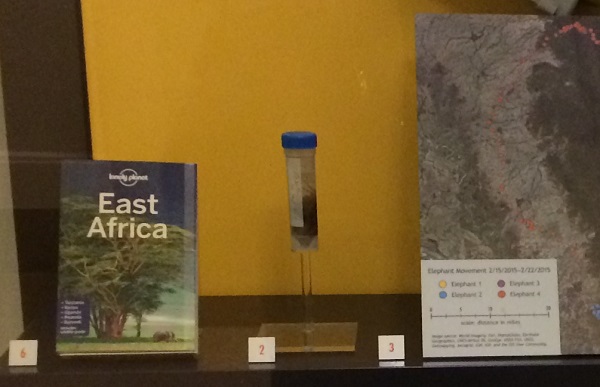

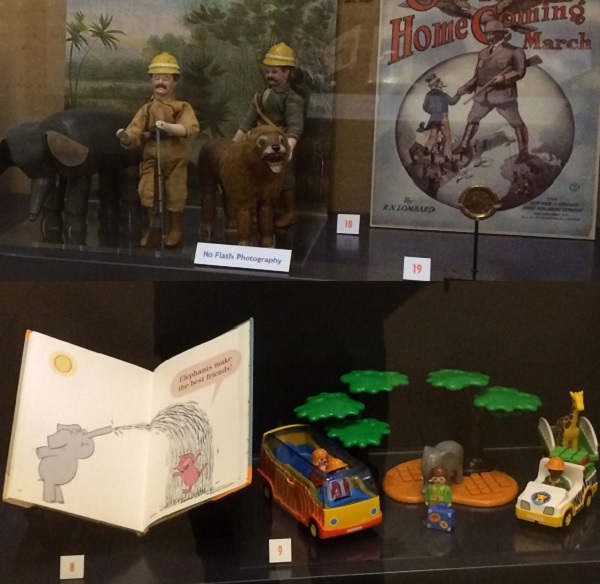

Game Change traces the shift in public attitudes about elephants from the late 19th century, an era when big game hunting was popular, to the critical conservation concerns of today.

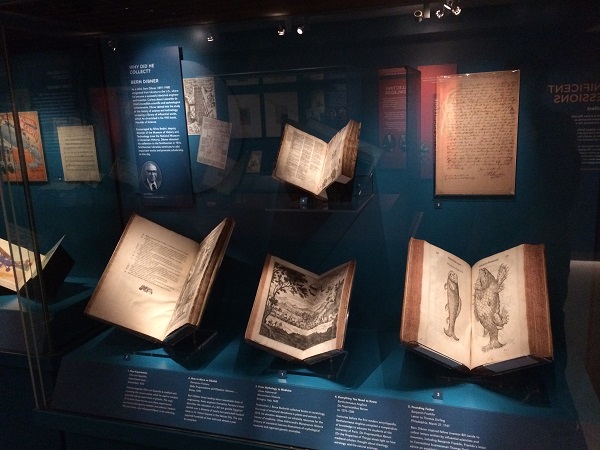

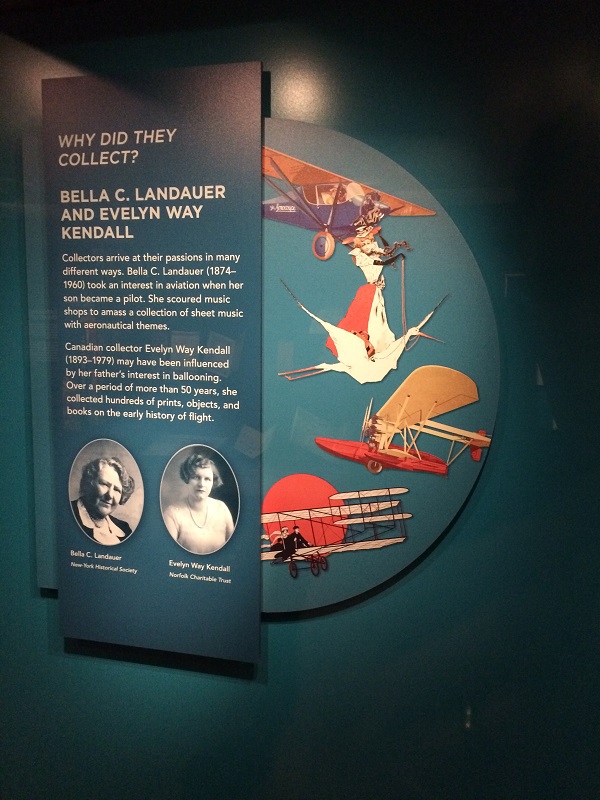

Magnificent Obsessions focuses on the pioneering collectors who shaped Smithsonian Libraries’ diverse collections in the areas of science, technology, history, art, and culture.

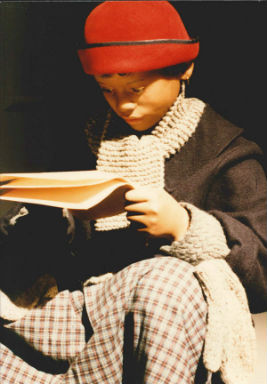

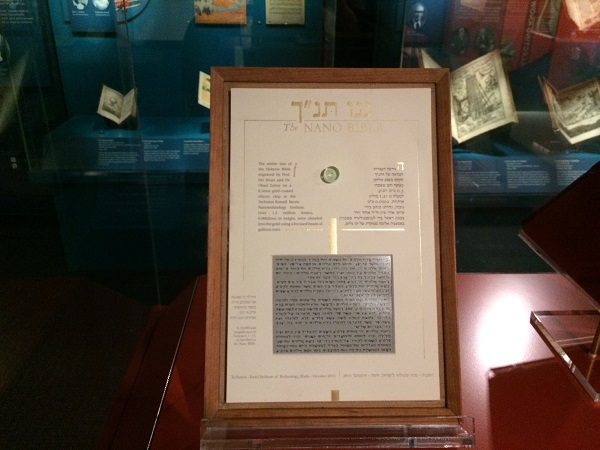

One of the biggest challenges in developing any exhibit is deciding what to include. This was particularly true of these exhibits. Smithsonian Libraries has a collection of more than two million volumes, including 50,000 rare books and manuscripts. Space constrains required curators to make difficult choices about what to cut. A hidden blessing for these exhibits was light. Because of paper’s sensitivity to light, pages must be turned and books must be rotated in and out of the exhibits over time, allowing additional content to be displayed. (Come back soon to see what’s new!)

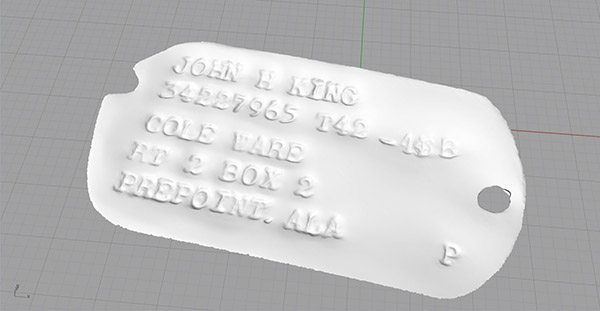

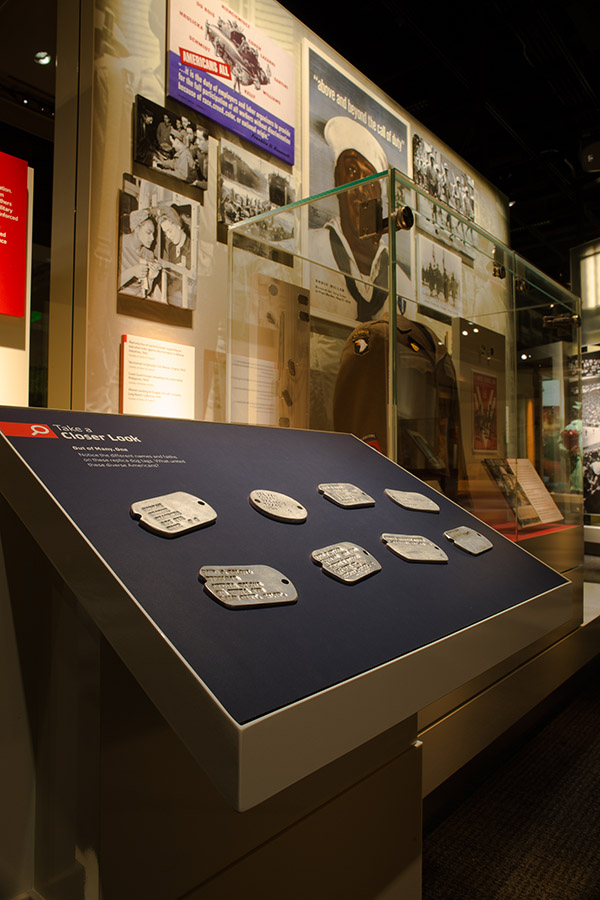

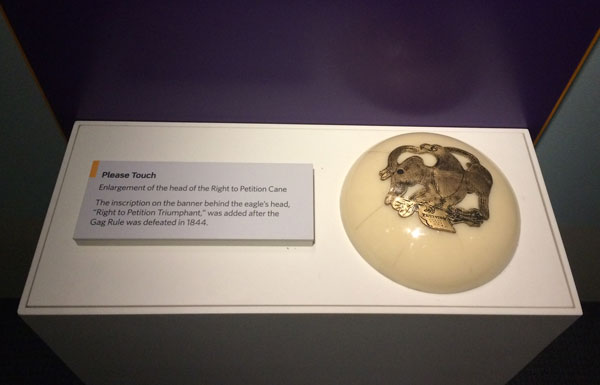

The books and artifacts featured in the exhibits show the incredible diversity of the Smithsonian’s collections.

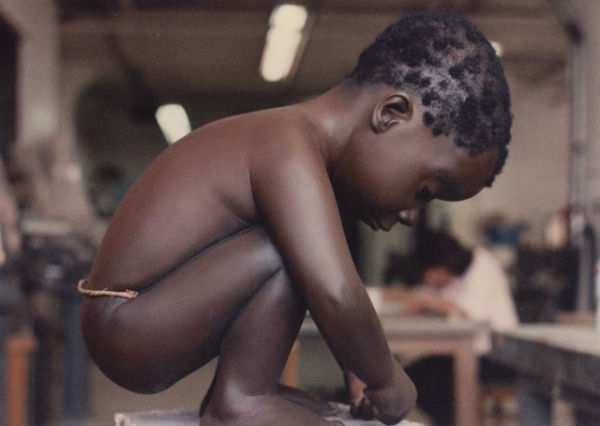

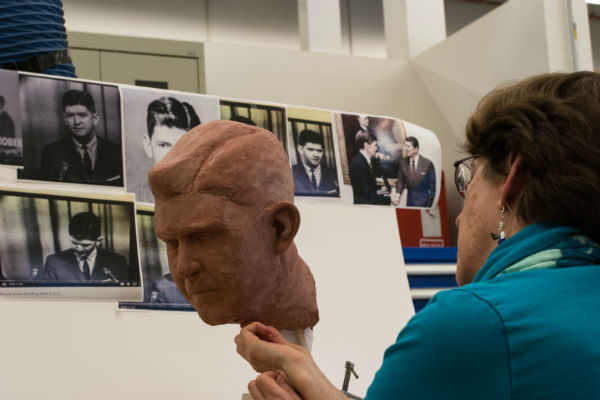

Of course, these exhibits are about more than just objects. The exhibit development team (including yours truly) wanted to go beyond the books to highlight the human stories they tell.

Game Change uses books and artifacts to show how humans’ attitudes about elephants have changed over time.

Magnificent Obsessions reveals the extraordinary passion collectors have for their subjects and explores what motivates them to collect.

We also wanted to open the conversation up to visitors by asking what they collect and why.

SIE’s design team included Elena Saxton on Game Change and Elena and Madeline Wan on Magnificent Obsessions. Elena and Madeline helped bring the stories to life with engaging designs and eye-catching graphics.

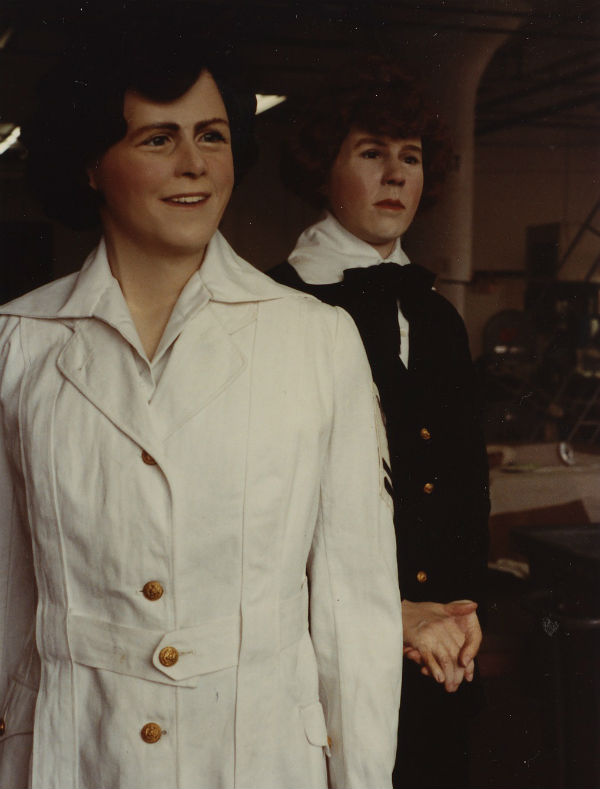

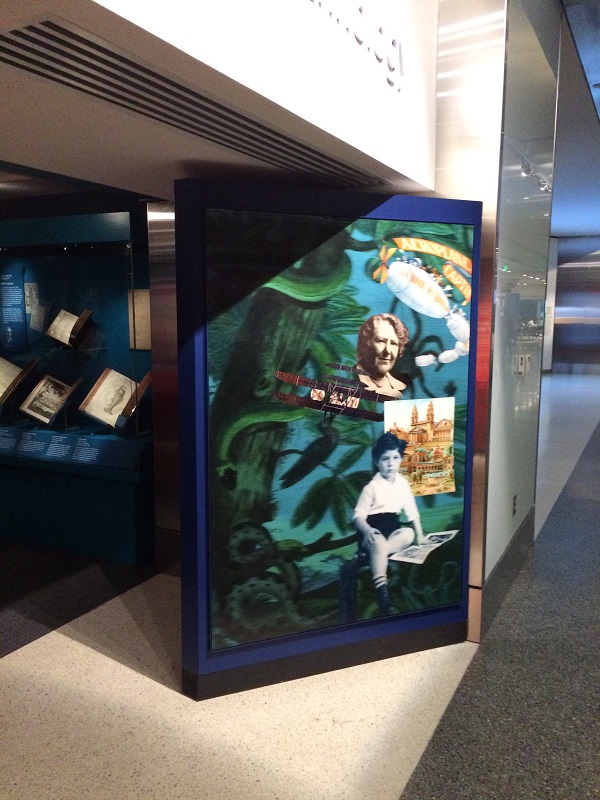

At the entrance to Magnificent Obsessions, the team created lenticular graphics, which change as you walk past them. These add movement and reveal the faces of the collectors behind the collections. Look out for a future blog post explaining how these were made.

SIE’s graphics team, including Evan Keeling, Mike Reed, and Scott Schmidt, printed and installed the graphics for both exhibits.

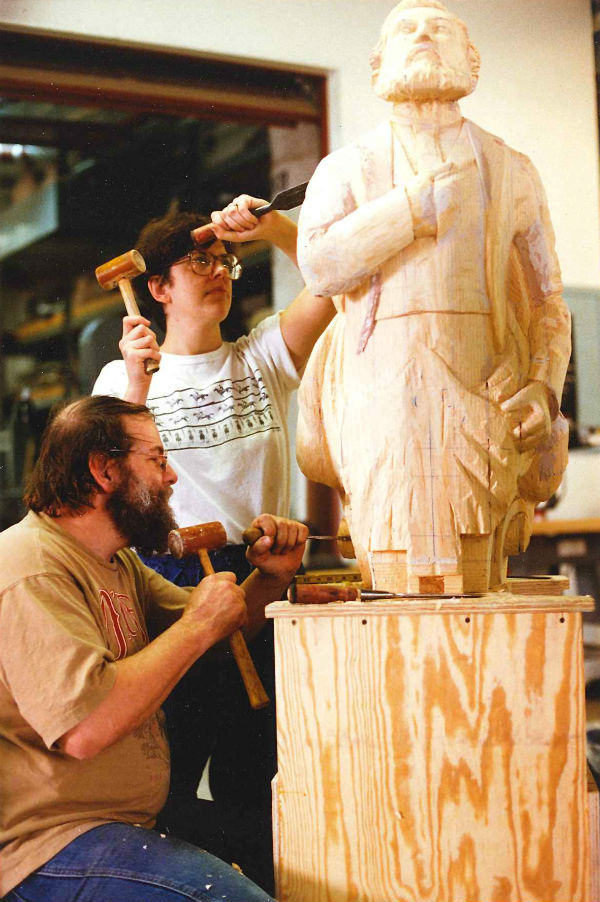

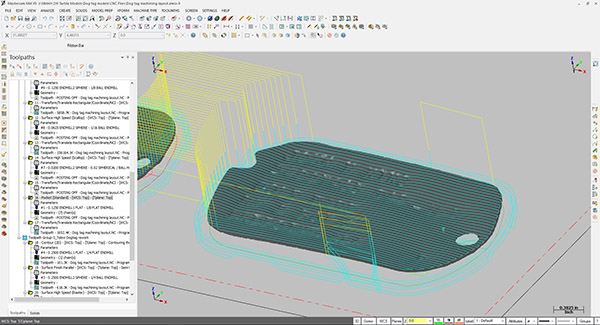

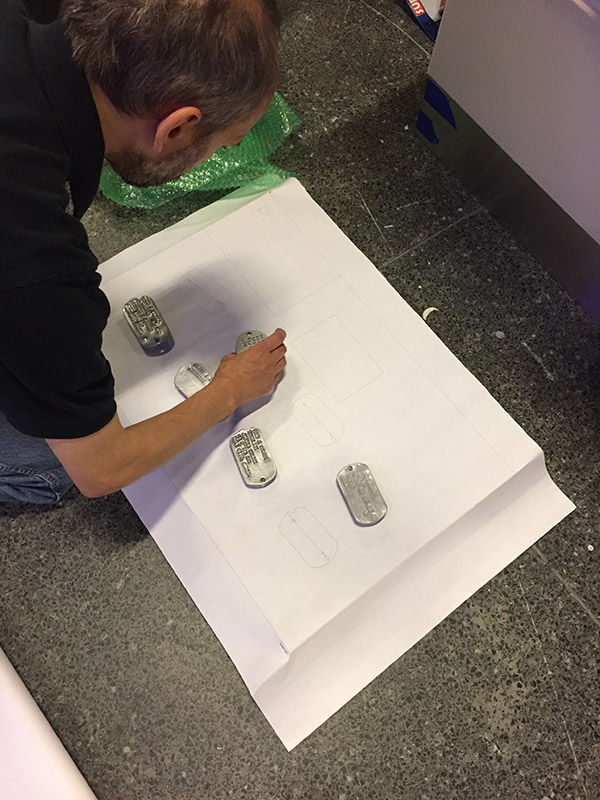

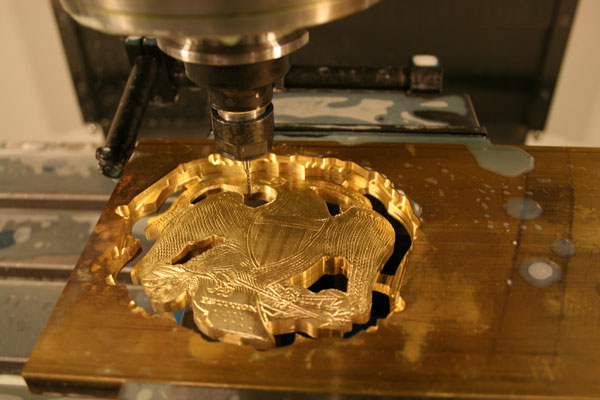

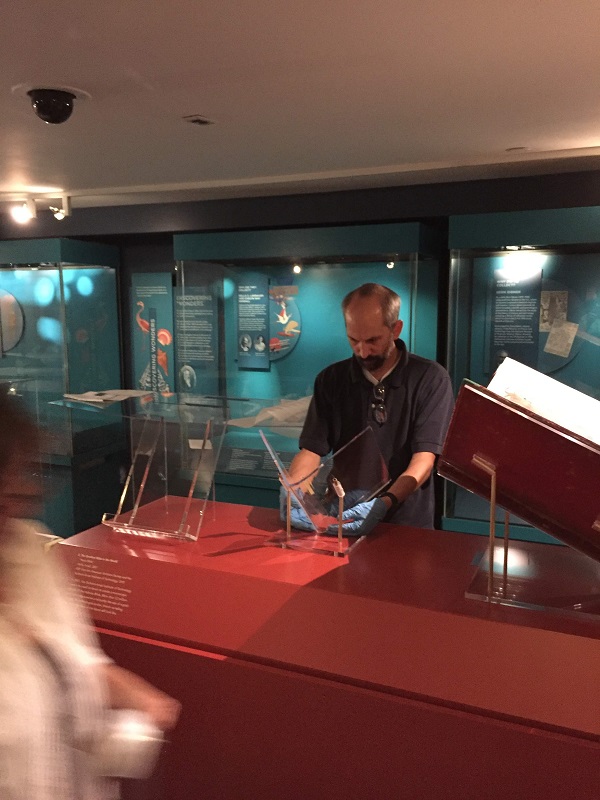

SIE’s 3D studio team members Chris Hollshwander and Danny Fielding worked with Vanessa Haight Smith, Head of Smithsonian Libraries Preservation Services, to make and install the mounts for the books and artifacts displayed in the exhibits.

Throughout it all, Smithsonian Libraries Exhibitions Program Coordinator Kirsten van der Veen and SIE Project Manager Betsy Robinson kept the team on track and on schedule—no easy feat, since the exhibits opened within weeks of each other!

Both exhibits are on display now. Please stop by and let us know what you think. In the meantime, we look forward to the next chapter of our collaboration with Smithsonian Libraries!