In September 2019, staff from Smithsonian Exhibits (SIE) and the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) traveled to Juneau, Alaska, to attend a Tlingit clan ceremony to dedicate a new clan hat—a replica made by SIE. You can watch the entire ceremony on the Sharing Our Knowledge conference website here.

The Tlingit are an indigenous people from southeastern Alaska. In Tlingit society, clans are divided into two distinct groups or moieties: Eagle/Wolf and Raven. The hat SIE worked on belongs to the Raven moiety. It is known as the sculpin hat (or Wéix’ s’áaxw in Tlingit language) for the fish it represents, which is an important crest symbol to the Kiks.ádi clan, to whom the hat belonged. In Tlingit culture, hats such as this one are sacred artifacts, known as At.óow, which are imbued with the spirits of their ancestors and used in dancing and ceremonies.

For SIE model maker Chris Hollshwander, the ceremony was more than just the end of another project. It was the culmination of a five-year journey, during which he was adopted into a Tlingit clan and immersed himself in learning about Tlingit culture.

The original sculpin hat was acquired by the Smithsonian in the 1880s and was probably even older. Unfortunately, the hat in the Smithsonian’s collection is broken and lacked important information. In 2012, a visiting Tlingit clan leader, Harold Jacobs, spotted the hat at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. He kick-started a seven-year process, which resulted in a replica of the hat being restored to the clan.

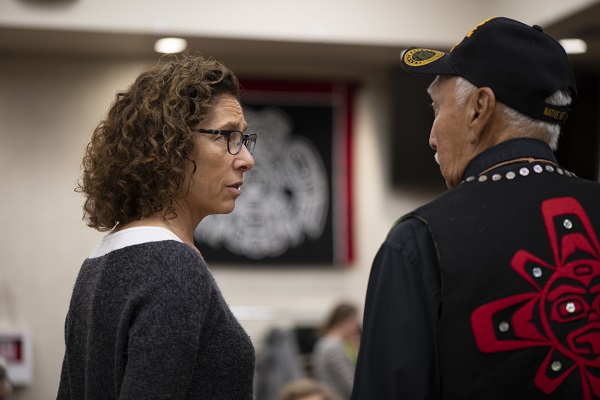

Staff from NMNH brought the original hat to the ceremony in September to accompany the reproduction. During the ceremony, clan members instilled a spirit into the new hat so that it could be danced again, more than 130 years after the original hat left. Chris, SIE director Susan Ades, and SIE model maker Carolyn Thome all attended the ceremony. During the celebration, Carolyn was formally recognized for her contributions and adopted into the Kiks.ádi clan. You can read an article about the ceremony here.

The ceremony was a fitting end to a long process, but how did SIE get involved in the first place?

Chris was introduced to the project in 2014, when clan leaders visiting NMNH interviewed him to get to know him better and gauge his level of interest in working on the hat. The goal was to create two replicas: one would be restored to the clan and used in ceremonies; the other would remain at NMNH, where it would be used for educational purposes. To the clan, it was important that whoever made the new hat for them should be a member of the Eagle/Wolf moiety. In order to work on the hat, Chris was adopted into the Kaagwaantaan (Wolf) clan, at a ceremony at NMNH a few days later by Kaagwaantaan clan leader Andrew Gamble.

You can read more about the background to this project in a blog post by Eric Hollinger, Tribal Liaison for NMNH’s Repatriation Office, who was involved in the project from the beginning and was instrumental in its success.

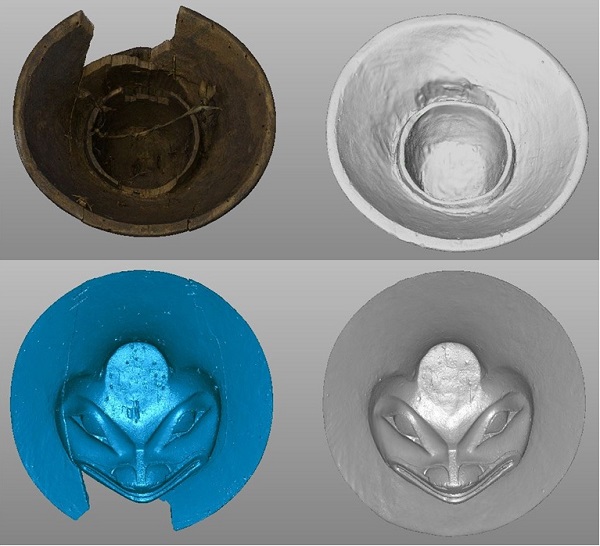

To prepare for the replicas to be made, NMNH took a CT scan of the original hat and partnered with the Smithsonian’s Digitization Program Office (DPO) to create a digital model by 3D scanning the hat with structured light scanners. They also took a series of photos, in a process known as photogrammetry, which would be processed into a digital model. You can take a virtual tour of the 3D model here.

Since the original hat was broken into multiple sections and had become warped over time, the first step was to repair it digitally. Using the files from DPO, Carolyn painstakingly repaired the hat through a process known as digital sculpting. She joined the cracks, bridged the gaps between the sections, and erased any non-original parts to prepare the 3D model for milling.

Meanwhile, the wood for the replicas needed to be sourced. The original hat was made of cedar. Since the clan intended to use their restored hat for dances, they decided to use alder, a stronger wood. The replica for the museum was to be made with yellow cedar. Both types of wood were harvested and shipped from Alaska, then had to be kept in freezers to avoid drying and cracking before the production of the replicas began.

To test the files and the machine settings, Chris milled a half-scale prototype of the hat, which he brought with him to Sitka, Alaska, in October 2017 to attend the Sharing Our Knowledge Conference.

The conference was a great opportunity for Chris to meet with clan members and learn more about their culture and traditions, while also demonstrating the Smithsonian’s 3D digitization and replication technology. You can read more about the conference here.

Once the clan approved the prototype, Chris got to work making the full-size replicas. Because the work was done at SIE’s facility in Landover, Maryland (nearly 3,000 miles away from Alaska), the Smithsonian used videoconferencing to allow clan representatives to watch the progress that was being made. Another example of modern technology at work!

One of the most challenging parts of the process was working with the wood and the number of machining set ups that were required. Because the wood was fresh, Chris needed to mill the pieces gradually over time, allowing the wood to slowly adjust in the freezer to avoid warping, cracking, and drying out too fast. The process involved roughing the hats out, then drying them slowly in a bed of their own wood chips outside of the freezer. When the wood was dried, Chris was able to do the final milling.

The final step was finishing the replicas under the supervision of Tlingit clan leader and artist Cyril Zuboff. Zuboff advised Chris and Eric on how to paint and attach materials to the hats, including shells, deer hide, sinew, ermine skins, and sea lion whiskers.

The Smithsonian Women’s Committee (SWC) generously funded the creation of the replicas through a grant. Members of the SWC came to meet with the project team and observe the finishing process.

You can watch a slideshow of the entire process here.

Image courtesy of NMNH.

After the replicas were completed, they remained at NMNH with the original hat. As preparations for the trip to the ceremony started over the summer, SIE provided a custom-fitted travel case for the alder hat. This will enable the hat to be transported to ceremonies in the future. SIE also fabricated a custom box for the original hat, to be couriered by NMNH Repatriation Office staff to Juneau.

When the hats were presented at the ceremony, clan members were thrilled with the results and were overjoyed to welcome home a part of their culture that had been away for more than 130 years. The new alder hat will eventually be brought to Sitka, Alaska, returning it to where it belongs for future generations. This project marks the first time that a traditional cultural object has been digitally restored and replicated and then dedicated as a sacred object by an indigenous community.

For Chris and Carolyn, adopted clan members, this has been more than just another project. It has been an experience that will stay with them for the rest of their lives.